HAPPY NEW YEAR 2024

ডI: চন্দন মোদক

অনুবাদক: প্ৰশান্ত বৰ্মন

কোভিদ-১৯ (COVID-19) কি?কোৰোণা ভাইৰাছ ৰোগ বা কোভিদ-১৯ (COVID-19) হৈছে SARS-COV-2 নামৰ ভাইৰাছৰ সংক্ৰমনৰ দ্বাৰা হোৱা ৰোগ। ই পোনপ্ৰথমে চিনৰ য়ুহান চহৰত ২০১৯ চনৰ শেষৰভাগত দেখা দিছিল। কিন্তু বহু কমসময়ৰ ভিতৰত সমগ্ৰ বিশ্বতে বিয়পিবলৈ ধৰে।এই ৰোগত আক্ৰান্ত লোকৰ গাত সাধাৰনতে জ্বৰ, কাহ আৰু উশাহ-নিশাহ লোৱাত অসুবিধা হোৱা দেখা যায়। হাওফাওত এই ভাইৰাছৰ সংক্ৰমনৰ ফলত নিউমোনিয়া (pneumonia) হোৱা দেখা যায় আৰু যাৰ ফলত উশাহ-নিশাহ লোৱাত কস্টকৰ হয়।

ই কেনেকৈ বিয়পে? কোৰোণা ভাইৰাছ প্ৰধানত এজন সংক্ৰমিত ব্যক্তিৰ পৰা কাঁহ বা হাচিৰ জৰিয়তে বিয়পে। ইয়াৰ সংক্ৰমন বিয়পিব পাৰে যদিহে কোনো ব্যক্তিয়ে ভাইৰাছ লাগি থকা কোনো পৃষ্ঠ চুই নিজৰ মুখ, নাক বা চকু স্পৰ্শ কৰে।ডক্তৰৰ মতে কোনো বেমাৰৰ লক্ষন নোহোৱা ব্যক্তিৰ পৰাও এই ভাইৰাছ বিয়পিব পাৰে।

কোভিদ-১৯ ৰ লক্ষনবোৰ কি কি?সাধাৰনতে কোনো ব্যক্তি ইয়াৰ দ্বাৰা সংক্ৰমন হ’লে কিছুদিন পিছতহে বেমাৰৰ লক্ষন সমুহ দেখা পোৱা যায়।ইয়াৰ লক্ষন সমুহ:

ইয়াৰ বাহিৰেও সংক্ৰমিত ব্যক্তিৰ গাত পানীলগা, মূৰৰ বিষ, ডিঙিৰ বিষ, গোন্ধ অনুভব নকৰা আদি লক্ষন ও দেখা পোৱা যায়। কিছুলোকৰ পেটৰ অসুবিধা যেনে ডায়েৰিয়া, বমিভাব আদি লক্ষন সমুহ পৰিলক্ষিত হয়।

সাধাৰনতে এক দুই সপ্তাহত এই লক্ষন সমুহ ভাল হ’বলৈ ধৰে কিন্তু কিছু লোকৰ ক্ষেত্ৰত কোভিদ-১৯ য়ে কিছু ভয়াবহ সমস্যা যেনে নিউমোনিয়া, হৃদৰোগ আদিৰ সৃস্টি কৰে যাৰ ফলত ৰোগীৰ মৃত্যু পৰ্যন্ত ঘটিব পাৰে। জেস্ঠলোকৰ ক্ষেত্ৰত এই অসুবিধা সমুহ বেছিকৈ পৰিলক্ষিত হয়। ইয়াৰ উপৰিও যিসকলে পূৰ্বৰে পৰা হৃদৰোগ, মধুমেহ, হাওফাওৰ সমস্যা বা কেন্সাৰৰ সৈতে যুজি আছে তেওলোকৰ ক্ষেত্ৰতো ই সমস্যাৰ সৃস্টি কৰে।

শিশু সকলকো কোৰোনো ভাইৰাছে আক্ৰমন কৰে যদিও তেওলোকৰ ক্ষেত্ৰত বেমাৰৰ লক্ষন সমুহ কমকৈ পৰিলক্ষিত হয়।

কেনেকৈ কোভিদ-১৯ প্ৰতিৰোধ কৰিব?কিছু বিশেষ নিয়মাবলী মানি চলিলে কোভিদ-১৯ প্ৰতিৰোধ কৰিব পৰা যায়। কোৰোনা ভাইৰাছৰ সংক্ৰমন হ্ৰাস কৰিবলৈ আমি তলত উল্লিখিত পদ্ধতিবোৰ অবলম্বন কৰিব লাগিব।

What is COVID-19?

Coronavirus disease 2019, or “COVID-19,” is an infection caused by a specific virus called SARS-CoV-2. The virus first appeared in late 2019 in the city of Wuhan, China. But it has spread quickly since then, and there are now cases in many other places, including Europe and the United States.

People with COVID-19 can have fever, cough, and trouble breathing. Problems with breathing happen when the infection affects the lungs and causes pneumonia.

Experts are studying this virus and will continue to learn more about it over time.

How is COVID-19 spread?

COVID-19 mainly spreads from person to person, similar to the flu. This usually happens when a sick person coughs or sneezes near other people. Doctors also think it is possible to get sick if you touch a surface that has the virus on it and then touch your mouth, nose, or eyes.

From what experts know so far, COVID-19 seems to spread most easily when people are showing symptoms. It is possible to spread it without having symptoms, too, but experts don’t know how often this happens.

What are the symptoms of COVID-19?Symptoms usually start a few days after a person is infected with the virus. But in some people it can take even longer for symptoms to appear.

Symptoms can include:

●Fever

●Cough

●Feeling tired

●Trouble breathing

●Muscle aches

Although it is less common, some people have other symptoms, such as headache, sore throat, runny nose, or problems with their sense of smell. Some have digestive problems like nausea or diarrhea.

For most people, symptoms will get better within a few weeks, and will not lead to long-term problems. Some people even have no symptoms at all. But in other people, COVID-19 can lead to serious problems like pneumonia, not getting enough oxygen, heart problems, or even death. This is more common in people who are older or have other health problems like heart disease, diabetes, lung disease, or cancer.

While children can get COVID-19, they seem less likely to have severe symptoms.

Should I see a doctor or nurse?

If you have a fever, cough, or trouble breathing and might have been exposed to COVID-19, call your doctor or nurse. You might have been exposed if any of the following happened within the last 14 days:

●You had close contact with a person who has the virus – This generally means being within about 6 feet of the person.

●You lived in, or traveled to, an area where lots of people have the virus.

If your symptoms are not severe, it is best to call your doctor, nurse, or clinic before you go in. They can tell you what to do and whether you need to be seen in person. Many people with only mild symptoms can stay home, and away from other people, until they get better. If you do need to go to the clinic or hospital, you will need to put on a face mask. The staff might also have you wait someplace away from other people.

If you are severely ill and need to go to the clinic or hospital right away, you should still call ahead. This way the staff can care for you while taking steps to protect others.

Your doctor or nurse will do an exam and ask about your symptoms. They will also ask questions about any recent travel and whether you have been around anyone who might be sick.

Will I need tests?

If your doctor or nurse suspects you have COVID-19, they might take a sample of fluid from inside your nose, and possibly your mouth, and send it to a lab for testing. If you are coughing up mucus, they might also test a sample of the mucus. These tests can show if you have COVID-19 or another infection.

In some areas, it might not be possible to test everyone who might have been exposed to the virus. If your doctor cannot test you, they might tell you to stay home and away from other people, and call if your symptoms get worse.

Your doctor might also order a chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan to check your lungs.

How is COVID-19 treated?

There is no specific treatment for COVID-19. Many people will be able to stay home while they get better, but people with serious symptoms or other health problems might need to go to the hospital:

●Mild illness – Most people with COVID-19 can rest at home until they get better. People with mild symptoms like fever and cough seem to get better after about 2 weeks, but it’s not the same for everyone.

If you are recovering from COVID-19, it’s important to stay home, and away from other people, until your doctor or nurse tells you it’s safe to go back to your normal activities. This decision will depend on how long it has been since you had symptoms, and in some cases, whether you have had a negative test (showing that the virus is no longer in your body).

●Severe illness – If you have more severe illness with trouble breathing, you might need to stay in the hospital, possibly in the intensive care unit (also called the “ICU”). While you are there, you will most likely be in a special “isolation” room. Only medical staff will be allowed in the room, and they will have to wear special gowns, gloves, masks, and eye protection.

The doctors and nurses can monitor and support your breathing and other body functions and make you as comfortable as possible. You might need extra oxygen to help you breathe easily. If you are having a very hard time breathing, you might need to be put on a ventilator. This is a machine to help you breathe.

Doctors are studying several different medicines to learn whether they might work to treat COVID-19. In certain cases, doctors might recommend these medicines.

Can COVID-19 be prevented?

There are things you can do to reduce your chances of getting COVID-19. These steps are a good idea for everyone, especially as the infection is spreading very quickly. But they are extra important for people age 65 years or older or who have other health problems. To help slow the spread of infection:

●Wash your hands with soap and water often. This is especially important after being in public and touching other people or surfaces. Make sure to rub your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds, cleaning your wrists, fingernails, and in between your fingers. Then rinse your hands and dry them with a paper towel you can throw away.

If you are not near a sink, you can use a hand gel to clean your hands. The gels with at least 60 percent alcohol work the best. But it is better to wash with soap and water if you can.

●Avoid touching your face with your hands, especially your mouth, nose, or eyes.

●Try to stay away from people who have any symptoms of the infection.

●Avoid crowds. If you live in an area where there have been cases of COVID-19, try to stay home as much as you can.

Even if you are healthy, limiting contact with other people can help slow the spread of disease. Experts call this “social distancing.” In general, the recommendation is to cancel or postpone large gatherings such as sports events, concerts, festivals, parades, and weddings. But even smaller gatherings can be risky. If you do need to be around other people, be sure to wash your hands often and avoid contact when you can. For example, you can avoid handshakes and high fives, and encourage others to do the same.

●Some experts recommend avoiding travel to certain countries where there are a lot of cases of COVID-19. Travel recommendations are changing often.

Experts do not recommend wearing a face mask if you are not sick, unless you are caring for someone who has (or might have) COVID-19.

There is a lot of information available about COVID-19, including rumors about how to avoid it. But not all of this information is accurate. For example, you might have heard that you can lower your risk using a hand dryer, rinsing out your nose with salt water, or taking antibiotics. These things do not work.

There is not yet a vaccine to prevent COVID-19.

What should I do if someone in my home has COVID-19?

If someone in your home has COVID-19, there are additional things you can do to protect yourself and others:

●Keep the sick person away from others – The sick person should stay in a separate room and use a separate bathroom if possible. They should also eat in their own room.

●Use face masks – The sick person should wear a face mask when they are in the same room as other people. If you are caring for the sick person, you can also protect yourself by wearing a face mask when you are in the room. This is especially important if the sick person cannot wear a mask.

●Wash hands – Wash your hands with soap and water often (see above).

●Clean often – Here are some specific things that can help:

•Wear disposable gloves when you clean. It’s also a good idea to wear gloves when you have to touch the sick person’s laundry, dishes, utensils, or trash.

•Regularly clean things that are touched a lot. This includes counters, bedside tables, doorknobs, computers, phones, and bathroom surfaces.

•Clean things in your home with soap and water, but also use disinfectants on appropriate surfaces. Some cleaning products work well to kill bacteria, but not viruses, so it’s important to check labels.

What should I do if there is a COVID-19 outbreak in my area?

The best thing you can do to stay healthy is to wash your hands regularly, avoid close contact with people who are sick, and stay home if you are sick. In addition, to help slow the spread of disease, it’s important to follow any official instructions in your area about limiting contact with other people. Even if there are no cases of COVID-19 where you live, that could change in the future.

When a lot of cases of COVID-19 spread through one area, experts call this “community transmission.” When this happens, schools or businesses in the area will likely close temporarily, and many events will be canceled. City and state leaders might also tell people to stay at home for some time. There are things you can do to prepare for this. For example, you might be able to work from home. You can also make sure you have a way to get in touch with relatives, neighbors, and others in your area. This way you will be able to receive and share information easily.

Rules and guidelines might be different in different areas. If officials do tell people in your area to stay home or avoid gathering with other people, it’s important to take this seriously and follow instructions as best you can. Even if you are not at high risk of getting very sick from COVID-19, you could still pass it along to others. Keeping people away from each other is one of the best ways to control the spread of the virus.

If you think you were in close contact with someone with COVID-19, but you don’t have any symptoms, you can call your local public health office. In the United States, this usually means your city or town’s Board of Health. Many states also have a “hotline” phone number you can call.

What can I do to cope with stress and anxiety?It is normal to feel anxious or worried about COVID-19. You can take care of yourself, and your family, by trying to:

●Take breaks from the news

●Get regular exercise and eat healthy foods

●Try to find activities that you enjoy and can do in your home

●Stay in touch with your friends and family members

Keep in mind that most people do not get severely ill or die from COVID-19. While it helps to be prepared, and it’s important to do what you can to lower your risk and help slow the spread of the virus, try not to panic.

Where can I go to learn more?

As we learn more about this virus, expert recommendations will continue to change. Check with your doctor or public health official to get the most updated information about how to protect yourself.

Understanding of COVID-19 is evolving. Interim guidance has been issued by the WHO and by the United States CDC.

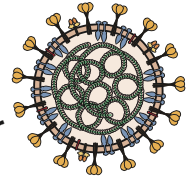

VIROLOGY: Full-genome sequencing and phylogenic analysis indicated that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 is a betacoronavirus in the same subgenus as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus (as well as several bat coronaviruses), but in a different clade. The structure of the receptor-binding gene region is very similar to that of the SARS coronavirus, and the virus has been shown to use the same receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), for cell entry.

The Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) virus, another betacoronavirus, appears more distantly related. The closest RNA sequence similarity is to two bat coronaviruses, and it appears likely that bats are the primary source; whether COVID-19 virus is transmitted directly from bats or through some other mechanism (eg, through an intermediate host) is unknown.

In a phylogenetic analysis of 103 strains of SARS-CoV-2 from China, two different types of SARS-CoV-2 were identified, designated type L (accounting for 70 percent of the strains) and type S (accounting for 30 percent). The L type predominated during the early days of the epidemic in China, but accounted for a lower proportion of strains outside of Wuhan than in Wuhan. The clinical implications of these findings are uncertain.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Geographic distribution — Globally, more than 7,00,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported. Since the first reports of cases from Wuhan, a city in the Hubei Province of China, at the end of 2019, more than 80,000 COVID-19 cases have been reported in China, with the majority of those from Hubei and surrounding provinces. A joint World Health Organization (WHO)-China fact-finding mission estimated that the epidemic in China peaked between late January and early February 2020, and the rate of new cases decreased substantially by early March.

However, cases have been reported in all continents, except for Antarctica, and have been steadily rising in many countries. These include the United States, most countries in Western Europe (including the United Kingdom), and Iran.

Immunity — Antibodies to the virus are induced in those who have become infected. Preliminary evidence suggests that some of these antibodies are protective, but this remains to be definitively established. Moreover, it is unknown whether all infected patients mount a protective immune response and how long any protective effect will last.

Data on protective immunity following COVID-19 are emerging but still in very early stages. One study derived monoclonal antibodies from convalescent patients’ B-cells that targeted the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein and had neutralizing activity in a pseudovirus model; another reported that rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2 did not develop reinfection following recovery and rechallenge. However, neither of these studies has been published in a peer reviewed journal, and further confirmation of these findings is needed.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Incubation period — The incubation period for COVID-19 is thought to be within 14 days following exposure, with most cases occurring approximately four to five days after exposure.

In a study of 1099 patients with confirmed symptomatic COVID-19, the median incubation period was four days (interquartile range two to seven days).

Using data from 181 publicly reported, confirmed cases in China with identifiable exposure, one modeling study estimated that symptoms would develop in 2.5 percent of infected individuals within 2.2 days and in 97.5 percent of infected individuals within 11.5 days. The median incubation period in this study was 5.1 days.

Spectrum of illness severity — The spectrum of symptomatic infection ranges from mild to critical; most infections are not severe. Specifically, in a report from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention that included approximately 44,500 confirmed infections with an estimation of disease severity:

●Mild (no or mild pneumonia) was reported in 81 percent.

●Severe disease (eg, with dyspnea, hypoxia, or >50 percent lung involvement on imaging within 24 to 48 hours) was reported in 14 percent.

●Critical disease (eg, with respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction) was reported in 5 percent.

●The overall case fatality rate was 2.3 percent; no deaths were reported among noncritical cases.

According to a joint World Health Organization (WHO)-China fact-finding mission, the case-fatality rate ranged from 5.8 percent in Wuhan to 0.7 percent in the rest of China. Most of the fatal cases occurred in patients with advanced age or underlying medical comorbidities

The proportion of severe or fatal infections may vary by location. As an example, in Italy, 12 percent of all detected COVID-19 cases and 16 percent of all hospitalized patients were admitted to the intensive care unit; the estimated case fatality rate was 7.2 percent in mid-March. In contrast, the estimated case fatality rate in mid-March in South Korea was 0.9 percent. This may be related to distinct demographics of infection; in Italy, the median age of patients with infection was 64 years, whereas in Korea the median age was in the 40s.

Risk factors for severe illness — Severe illness can occur in otherwise healthy individuals of any age, but it predominantly occurs in adults with advanced age or underlying medical comorbidities.

Comorbidities that have been associated with severe illness and mortality include :

●Cardiovascular disease

●Diabetes mellitus

●Hypertension

●Chronic lung disease

●Cancer

●Chronic kidney disease

In a subset of 355 patients who died with COVID-19 in Italy, the mean number of pre-existing comorbidities was 2.7, and only 3 patients had no underlying condition.

Particular laboratory features have also been associated with worse outcomes. These include:

●Lymphopenia

●Elevated liver enzymes

●Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

●Elevated inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein [CRP], ferritin)

●Elevated D-dimer (>1 mcg/mL)

●Elevated prothrombin time (PT)

●Elevated troponin

●Elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK)

●Acute kidney injury

As an example, in one study, progressive decline in the lymphocyte count and rise in the D-dimer over time were observed in nonsurvivors compared with more stable levels in survivors.

Impact of age — Individuals of any age can acquire severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, although adults of middle age and older are most commonly affected.

In Chin, Older age was also associated with increased mortality, with case fatality rates of 8 and 15 percent among those aged 70 to 79 years and 80 years or older, respectively. Similar findings were reported from Italy, with case fatality rates of 12 and 20 percent among those aged 70 to 79 years and 80 years or older, respectively. Similarly, in the United States, mortality was highest among older individuals, with 80 percent of deaths occurring in those aged ≥65 years.

In the large Chinese report described above, only 2 percent of infections were in individuals younger than 20 years old. Similarly, in South Korea, only 6.3 percent of nearly 8000 infections were in those younger than 20 years old. In a small study of 10 children in China, clinical illness was mild; 8 had fever, which resolved within 24 hours, 6 had cough, 4 had sore throat, 4 had evidence of focal pneumonia on CT, and none required supplemental oxygen. In another study of six children aged 1 to 7 years who were hospitalized in Wuhan with COVID-19, all had fever >102.2°F/39°C and cough, four had imaging evidence of viral pneumonia, and one was admitted to the intensive care unit; all children recovered.

Asymptomatic infections — Asymptomatic infections have also been described, but their frequency is unknown.

In a COVID-19 outbreak on a cruise ship where nearly all passengers and staff were screened for SARS-CoV-2, approximately 17 percent of the population on board tested positive as of February 20; about half of the 619 confirmed COVID-19 cases were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. A modeling study estimated that 18 percent were true asymptomatic cases (ie, did not go on to develop symptoms).

Clinical manifestations

Initial presentation — Pneumonia appears to be the most frequent serious manifestation of infection, characterized primarily by fever, cough, dyspnea, and bilateral infiltrates on chest Xray. There are no specific clinical features that can yet reliably distinguish COVID-19 from other viral respiratory infections.

In a study describing 138 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, the most common clinical features at the onset of illness were :

●Fever in 99 percent

●Fatigue in 70 percent

●Dry cough in 59 percent

●Anorexia in 40 percent

●Myalgias in 35 percent

●Dyspnea in 31 percent

●Sputum production in 27 percent

Other, less common symptoms have included headache, sore throat, and rhinorrhea. In addition to respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, nausea and diarrhea) have also been reported; and in some patients, they may be the presenting complaint.

Course and complications —Some patients with initially mild symptoms may progress over the course of a week. In one study of 138 patients hospitalized in Wuhan for pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2, dyspnea developed after a median of five days since the onset of symptoms, and hospital admission occurred after a median of seven days of symptoms. In another study, the median time to dyspnea was eight days.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a major complication in patients with severe disease and can manifest shortly after the onset of dyspnea. In the study of 138 patients described above, ARDS developed in 20 percent a median of eight days after the onset of symptoms; mechanical ventilation was implemented in 12.3 percent]. In another study of 201 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, 41 percent developed ARDS; age greater than 65 years, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension were each associated with ARDS.

Other complications have included arrhythmias, acute cardiac injury, and shock. In one study, these were reported in 17, 7, and 9 percent, respectively. In a series of 21 severely ill patients admitted to the ICU in the United States, one-third developed cardiomyopathy.

According to the WHO, recovery time appears to be around two weeks for mild infections and three to six weeks for severe disease.

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Clinical suspicion and criteria for testing — The possibility of COVID-19 should be considered primarily in patients with new onset fever and/or respiratory tract symptoms (eg, cough, dyspnea). It should also be considered in patients with severe lower respiratory tract illness without any clear cause. Although these syndromes can occur with other viral respiratory illnesses, the likelihood of COVID-19 is increased if the patient:

●Resides in or has traveled within the prior 14 days to a location where there is community transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or

●Has had close contact with a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 in the prior 14 days, including through work in health care settings. Close contact includes being within approximately six feet (about two meters) of a patient for a prolonged period of time while not wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) or having direct contact with infectious secretions while not wearing PPE.

The diagnosis cannot be definitively made without microbiologic testing, but limited capacity may preclude testing all patients with suspected COVID-19. Local health departments may have specific criteria for testing.

Laboratory testing — Patients who meet the testing criteria discussed above should undergo testing for SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) in addition to testing for other respiratory pathogens.

In the United States, the CDC recommends collection of a nasopharyngeal swab specimen to test for SARS-CoV-2. An oropharyngeal swab can be collected but is not essential; if collected, it should be placed in the same container as the nasopharyngeal specimen. Oropharyngeal, nasal mid-turbinate, or nasal swabs are acceptable alternatives if nasopharyngeal swabs are unavailable.

Expectorated sputum should be collected from patients with productive cough; induction of sputum is not recommended. A lower respiratory tract aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage should be collected from patients who are intubated.

In a study of 205 patients with COVID-19 who were sampled at various sites, the highest rates of positive viral RNA tests were reported from bronchoalveolar lavage (95 percent, 14 of 15 specimens) and sputum (72 percent, 72 of 104 specimens), compared with oropharyngeal swab (32 percent, 126 of 398 specimens).

S-CoV-2 RNA is detected by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). A positive test for SARS-CoV-2 generally confirms the diagnosis of COVID-19, although false-positive tests are possible.

If initial testing is negative but the suspicion for COVID-19 remains, the WHO recommends resampling and testing from multiple respiratory tract sites. The accuracy and predictive values of SARS-CoV-2 testing have not been systematically evaluated. Negative RT-PCR tests on oropharyngeal swabs despite CT findings suggestive of viral pneumonia have been reported in some patients who ultimately tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Serologic tests, once generally available, should be able to identify patients who have either current or previous infection but a negative PCR test.

For safety reasons, specimens from a patient with suspected or documented COVID-19 should not be submitted for viral culture.

MANAGEMENT

Home care — Home management is appropriate for patients with mild infection who can be adequately isolated in the outpatient setting . Management of such patients should focus on prevention of transmission to others and monitoring for clinical deterioration, which should prompt hospitalization.

Outpatients with COVID-19 should stay at home and try to separate themselves from other people and animals in the household. They should wear a facemask when in the same room (or vehicle) as other people and when presenting to health care settings. Disinfection of frequently touched surfaces is also important.The optimal duration of home isolation is uncertain.

●When a test-based strategy is used, patients may discontinue home isolation when there is:

•Resolution of fever without the use of fever-reducing medications AND

•Improvement in respiratory symptoms (eg, cough, shortness of breath) AND

•Negative results of a US FDA Authorized molecular assay for COVID-19 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected ≥24 hours apart (total of two negative specimens)

●When a non-test-based strategy is used, patients may discontinue home isolation when the following criteria are met:

•At least seven days have passed since symptoms first appeared AND

•At least three days (72 hours) have passed since recovery of symptoms (defined as resolution of fever without the use of fever-reducing medications and improvement in respiratory symptoms [eg, cough, shortness of breath])

In some cases, patients may have had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, but they did not have any symptoms when they were tested. In such patients, home isolation may be discontinued when at least seven days have passed since the date of their first positive COVID-19 test so long as there was no evidence of subsequent illness.

Hospital care — Some patients with suspected or documented COVID-19 have severe disease that warrants hospital care. Patients with severe disease often need oxygenation support. High-flow oxygen and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation have been used, but the safety of these measures is uncertain, and they should be considered aerosol-generating procedures that warrant specific isolation precautions.

Some patients may develop acute respiratory distress syndrome and warrant intubation with mechanical ventilation.

PREVENTION

Infection control for suspected or confirmed cases — Infection control to limit transmission is an essential component of care in patients with suspected or documented COVID-19.

Individuals with suspected infection in the community should be advised to wear a medical mask to contain their respiratory secretions prior to seeking medical attention. In the health care setting, the World Health Organization (WHO) and CDC recommendations for infection control for suspected or confirmed infections differ slightly:

Any personnel entering the room of a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should wear the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE): gown, gloves, eye protection, and a respirator (eg, an N95 respirator). If supply of respirators is limited, the CDC acknowledges that facemasks are an acceptable alternative (in addition to contact precautions and eye protection), but respirators should be worn during aerosol-generating procedures.

Aerosol-generating procedures include tracheal intubation, noninvasive ventilation, tracheotomy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, manual ventilation before intubation, upper endoscopy, and bronchoscopy. The CDC does not consider nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal specimen collection an aerosol-generating procedure that warrants an airborne isolation room, but it should be performed in a single-occupancy room with the door closed, and any personnel in the room should wear a respirator (or if unavailable, a facemask).

Preventing exposure in the community — The following general measures are recommended to reduce transmission of infection:

●Diligent hand washing, particularly after touching surfaces in public. Use of hand sanitizer that contains at least 60 percent alcohol is a reasonable alternative if the hands are not visibly dirty.

●Respiratory hygiene (eg, covering the cough or sneeze).

●Avoiding touching the face (in particular eyes, nose, and mouth).

●Avoiding crowds (particularly in poorly ventilated spaces) if possible and avoiding close contact with ill individuals.

●Cleaning and disinfecting objects and surfaces that are frequently touched.

In particular, older adults and individuals with chronic medical conditions should be encouraged to follow these measures.

Women who choose not to breastfeed must take similar precautions to prevent transmission through close contact when formula is used.

Managing chronic medications

Patients receiving ACE inhibitors/ARBs — Patients receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) should continue treatment with these agents.

Patients receiving immunomodulatory agents — Immunocompromised patients with COVID-19 are at increased risk for severe disease, and the decision to discontinue steroid, biologics, or other immuno-suppressive drugs in the setting of infection must be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Here are the patient education articles that are relevant to this topic. We encourage you to print or e-mail these topics to your patients. (You can also locate patient education articles on a variety of subjects by searching on “patient info” and the keyword(s) of interest.)

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

●The possibility of COVID-19 should be considered primarily in patients with fever and/or respiratory tract symptoms who reside in or have traveled to areas with community transmission or who have had recent close contact with a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19. Clinicians should also be aware of the possibility of COVID-19 in patients with severe respiratory illness when no other etiology can be identified.

●In addition to testing for other respiratory pathogens, a nasopharyngeal swab specimen should be collected for reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing for SARS-CoV-2.

●Upon suspicion of COVID-19, CDC recommends a single-occupancy room for patients and gown, gloves, eye protection, and a respirator (or facemask as an alternative) for health care personnel.

●Management consists of supportive care, although investigational approaches are being evaluated. Home management may be possible for patients with mild illness who can be adequately isolated in the outpatient setting.

●To reduce the risk of transmission in the community, individuals should be advised to wash hands diligently, practice respiratory hygiene (eg, cover their cough), and avoid crowds and close contact with ill individuals, if possible. Facemasks are not routinely recommended for asymptomatic individuals to prevent exposure in the community. Social distancing is advised, particularly in locations that have community transmission.

CORONA VIRUS DISEASE (COVID 19) is caused by a member of the coronavirus family that has never been encountered before. Like other coronaviruses, it has transferred to humans from animals. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared it a pandemic.

Coronaviruses are important human and animal pathogens. At the end of 2019, a novel coronavirus was identified as the cause of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, a city in the Hubei Province of China. It rapidly spread, resulting in an epidemic throughout China, followed by an increasing number of cases in other countries throughout the world. In February 2020, the World Health Organization designated the disease COVID-19, which stands for coronavirus disease 2019. The virus that causes COVID-19 is designated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); previously, it was referred to as 2019-nCoV.

The new coronavirus, provisionally called 2019-nCoV, that originated in China has spread globally with approximately seven lakh confirmed cases worldwide and death toll of more than 30,800 till the time of writing this article. Slowly COVID 19 is spreading in India and now case burden is more than thousand and death toll is 25 till now and increasing day by day.

What was the origin of the virus?

The virus was first isolated by infection of cells in culture with broncho-alveolar wash from a patient in Wuhan with pneumonia. The infected cells showed cytopathic effects, and staining of cells with an antibody to coronavirus NP protein, which is conserved among coronaviruses, revealed intracellular staining.

The complete genome sequence of this isolate was determined (29,891 bases) and comparison with genomes of other coronaviruses revealed that it is most closely related (96.2% identity) with viral RNA from a Rhinolophus affinis bat obtained in Yunnan Province in 2013. This finding means that both viruses have a common ancestor in bats. Recall that SARS-CoV also originated in bats. Many coronaviruses circulate in bats and more are likely to cross into humans in the future.

How the virus entered humans from bats is unknown.

According to current evidence, COVID-19 virus is transmitted between people through respiratory droplets and contact routes.1

Droplet transmission occurs when a person is in in close contact (within 1 m) with someone who has respiratory symptoms (e.g. coughing or sneezing,) and is therefore at risk of having his/her mucosae (mouth and nose) or conjunctiva (eyes) exposed to potentially infective respiratory droplets (which are generally considered to be > 5-10 μm in diameter). Droplet transmission may also occur through fomites in the immediate environment around the infected person. Therefore, transmission of the virus can occur by direct contact with infected people and indirect contact with surfaces in the immediate environment or with objects used on the infected person (e.g. stethoscope or thermometer).

Airborne transmission is different from droplet transmission as it refers to the presence of microbes within droplet nuclei, which are generally considered to be particles < 5μm in diameter, and which result from the evaporation of larger droplets or exist within dust particles. They may remain in the air for long periods of time and be transmitted to others over distances greater than 1 meter.

In the context of COVID-19, airborne transmission may be possible in specific circumstances and settings in which procedures that generate aerosols are performed (i.e. endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, open suctioning, administration of nebulized treatment, manual ventilation before intubation, turning the patient to the prone position, disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation, tracheostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation). In analysis of 75,465 COVID-19 cases in China, airborne transmission was not reported.

There is some evidence that COVID-19 infection may lead to intestinal infection and be present in faeces. However, to date only one study has cultured the COVID-19 virus from a single stool specimen. There have been no reports of faecal−oral transmission of the COVID-19 virus to date.

Implications of recent findings of detection of COVID-19 virus from air sampling . These initial findings need to be interpreted carefully.

A recent publication in the New England Journal of Medicine has evaluated virus persistence of the COVID-19 virus.9 In this experimental study, aerosols were generated using a three-jet Collison nebulizer and fed into a Goldberg drum

under controlled laboratory conditions. This is a high-powered machine that does not reflect normal human cough conditions. Further, the finding of COVID-19 virus in aerosol particles up to 3 hours does not reflect a clinical setting in which aerosol-generating

procedures are performed—that is, this was an experimentally induced aerosol-generating procedure.

There are reports from settings where symptomatic COVID-19 patients have been admitted and in which nov COVID 19 RNA was detected in air samples. In addition, it is important to note that the detection of RNA in environmental samples based on PCR-based assays is not indicative of viable virus that could be transmissible.

Based on the available evidence, including the recent publications mentioned above, WHO continues to recommend droplet and contact precautions for those people caring for COVID-19 patients and contact and airborne precautions for circumstances and settings in which aerosol generating procedures are performed. These recommendations are consistent with other national and international guidelines, including those developed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and Society of Critical Care Medicine1 and those currently used in Australia, Canada, and United Kingdom.

At the same time, other countries and organizations, including the US Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, recommend airborne precautions for any situation involving the care of COVID-19 patients, and consider the use of medical masks as an acceptable option in case of shortages of respirators (N95, FFP2 or FFP3).1

Current WHO recommendations emphasize the importance of rational and appropriate use of all PPE, not only masks, which requires correct and rigorous behavior from health care workers, particularly in doffing procedures and hand hygiene practices. WHO also recommends staff training on these recommendations, as well as the adequate procurement and availability of the necessary PPE and other supplies and facilities. Finally, WHO continues to emphasize the utmost importance of frequent hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and environmental cleaning and disinfection, as well as the importance of maintaining physical distances and avoidance of close, unprotected contact with people with fever or respiratory symptoms.

Period of infectivity

The interval during which an individual with COVID-19 is infectious is uncertain. Most data informing this issue are from studies evaluating viral RNA detection from respiratory and other specimens. However, detection of viral RNA does not necessarily indicate the presence of infectious virus.

Viral RNA levels appear to be higher soon after symptom onset compared with later in the illness; this raises the possibility that transmission might be more likely in the earlier stage of infection, but additional data are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The duration of viral shedding is also variable; there appears to be a wide range, which may depend on severity of illness. In one study of 21 patients with mild illness (no hypoxia), 90 percent had repeated negative viral RNA tests on nasopharyngeal swabs by 10 days after the onset of symptoms; tests were positive for longer in patients with more severe illness. In another study of 137 patients who survived COVID-19, the median duration of viral RNA shedding from oropharyngeal specimens was 20 days (range of 8 to 37 days) .

The reported rates of transmission from an individual with symptomatic infection vary by location and infection control interventions. According to a joint WHO-China report, the rate of secondary COVID-19 ranged from 1 to 5 percent among tens of thousands of close contacts of confirmed patients in China. Among crew members on a cruise ship, 2 percent developed confirmed infection . In the United States, the symptomatic secondary attack rate was 0.45 percent among 445 close contacts of 10 confirmed patients.

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from asymptomatic individuals (or individuals within the incubation period) has also been described. However, the extent to which this occurs remains unknown. Large-scale serologic screening may be able to provide a better sense of the scope of asymptomatic infections and inform epidemiologic analysis; several serologic tests for SARS-CoV-2 are under development.

People may be sick with the virus for 1 to 14 days before developing symptoms. According to the WHO, the most common symptoms of Covid-19 are fever, tiredness and a dry cough. Some patients may also have a runny nose, sore throat, nasal congestion and aches and pains or diarrhoea. Some people report losing their sense of taste and/or smell. About 80% of people who get Covid-19 experience a mild case – about as serious as a regular cold – and recover without needing any special treatment. More rarely, the disease can be serious and even fatal.

About one in six people, the WHO says, become seriously ill. The elderly and people with underlying medical problems like high blood pressure, heart problems or diabetes, or chronic respiratory conditions, cancer patients, patients getting immuno-suppressants are at a greater risk of serious illness from Covid-19.

Specific symptoms:

Is there any treatment?

As this is viral pneumonia, antibiotics are of no use. The antiviral drugs we have against flu will not work, and there is currently no vaccine. Recovery depends on the strength of the immune system.

Yes. You should go for testing your samples in the nearby center for diagnosis. At the same time anyone with symptoms should stay at home as self quarantine for at least 7 days. If you live with other people, they should stay at home for at least 14 days, to avoid spreading the infection outside the home. This applies to everyone, regardless of whether they have travelled abroad.

HOW TO PREVENT THIS DREADED COVID 19?

There’s currently no vaccine to prevent coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Only way to stop this epidemic is to stop man to man transmission. That’s why Govt of India and other states have announced complete lock down.

You can protect yourself and help prevent spreading the virus to others if you:

Do

Wash your hands regularly for 20 seconds, with soap and water or alcohol-based hand rub

Cover your nose and mouth with a disposable tissue or flexed elbow when you cough or sneeze

Avoid close contact (1 meter or 3 feet) with other people

Stay home and self-isolate from others

Don’t

Touch your eyes, nose, or mouth if your hands are not clean